Earlier this year, we published findings from a 2016 national survey of family practitioners (FPs), internists, obstetricians/gynecologists (OB-GYNs), and nurse practitioners (NPs) (total n = 1,506) indicating that most health care professionals (HCPs) lack basic knowledge of current guidelines for the non-surgical treatment of obesity. In addition to knowledge-related items, we fielded questions to assess HCP beliefs about the causes of obesity, the perceived effectiveness of obesity counseling techniques, and the prevalence of in-office accommodations for patients with obesity in their practices.

#1: Providers indicated that obesity is a matter of personal responsibility.

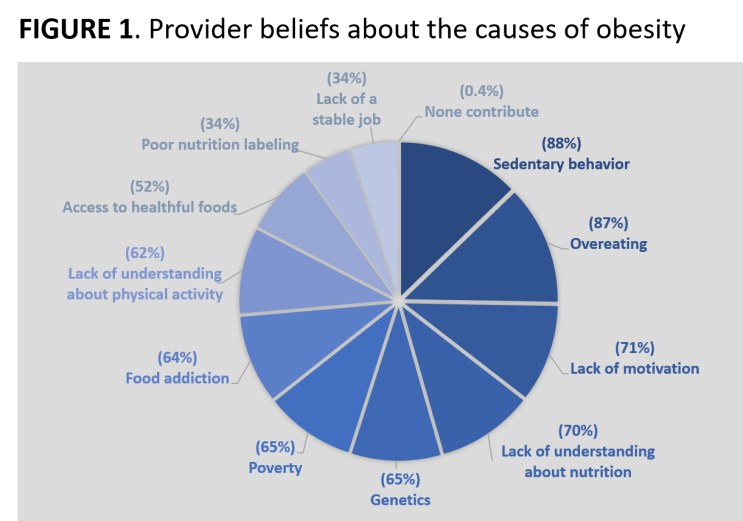

When asked to consider the causes of clinical obesity and select those they believed were the most likely contributors to obesity, sedentary behavior, overeating, and lack of motivation emerged as the top responses (Figure 1). Recognition of social determinants of health (e.g. poverty, food insecurity, unstable job) as contributors to obesity did not differ significantly by provider type. Female FPs and internists were significantly more likely than their male counterparts to indicate social determinants as likely contributors to obesity (p < .01). For all provider types, a higher level of composite knowledge (total number of guidelines correctly identified) was associated with selection of a greater number of possible causes of obesity.

#2: Knowledge of obesity care guidelines was associated with providing a greater number of office accommodations for patients with obesity.

The average number of accommodations instituted in their practice was highest among NP and lowest among internists (controlling for practice setting). Among internists and OB-GYNs, but not NPs and FPs, increased knowledge was associated with providing a larger number of in-office accommodations for patients with obesity. Across all provider types, larger-size blood pressure cuffs, wheelchair accessible bathrooms, and extra-large gowns were the most frequently cited accommodations. Only 30% of HCPs indicated that scales are placed in private areas.

#3: A strong, positive association was found between accommodations for patients with obesity and the perceived efficacy of multiple obesity counseling strategies

HCPs were most likely to identify motivational interviewing (51%) and the 5As framework (ask, assess, assist, arrange, advise) (39%) as effective counseling strategies. Only 25% of respondents indicated that person-first language is useful when counseling on obesity. Across all provider types, identification of a larger number of effective counseling techniques was associated with more office accommodations for patients with obesity. Providers who correctly identified the USPSTF and guideline-recommended intensity of obesity counseling as approximately twice-monthly for at least six months were significantly more likely than providers unfamiliar with the guideline to identify motivational interviewing as an effective obesity counseling strategy (p < .05).

The results of our analyses suggest that knowledge is independently associated with provider beliefs about the causes of obesity and the perceived effectiveness of obesity counseling techniques, consistent with the notion that providers who recognize obesity as a complex, multifactorial disease may be more likely to familiarize themselves with the appropriate provision of guideline-recommended obesity treatments. Our findings align well with previous literature that indicates weight stigma and bias among health professionals negatively impacts patient care. Waiting areas and examination rooms that are poorly equipped to care for bodies of all shapes and sizes perpetuate weight bias and constitute additional barriers to effective care. Respectful office accommodations for patients with obesity should be instituted by providers and health care systems to reduce the stigmatization among their patients with obesity.

HCP Beliefs About Causes, Accommodations & Techniques

June 1, 2018