In January we celebrated the 2-year anniversary of the release of the Lancet Commission on Obesity report, entitled “The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition and Climate Change.” The report focuses on the contributions of the food and agriculture, urban design, land use, and transportation systems, and the triple duty solutions to mitigate their contributions to the Global Syndemic. For example, the transportation sector in the U.S. generates approximately 30% of the US greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). Increased GHGs raise the earth’s mean surface temperature, which reduces the protein and micronutrient content of crops and crop yields, which contribute to food insecurity and undernutrition in the developing world.

Eliminating the subsidies and tax breaks for fossil fuel production would increase the costs of gasoline, which would lead to reduced car use and increases in public transportation, walking and biking, and reduce the GHG emissions from the transportation system. Increased physical and public transport would help prevent obesity and sustain weight maintenance. On the food and agriculture side, reduced demand for beef would reduce beef production which would reduce methane, a powerful GHG produced by cattle, and reduce the contribution of meat to colon cancer, cardiovascular disease and obesity. An emphasis on dietary changes to mitigate climate change could be viewed as a stealth intervention for obesity, particularly among young adults.

The changes required to shift dietary and activity patterns present a major challenge. Eliminating subsidies for agriculture and fossil fuels will require massive disruptions. Policy resistance will continue until sufficient political will is generated to change these practices. So the question becomes, how do we generate the necessary political will?

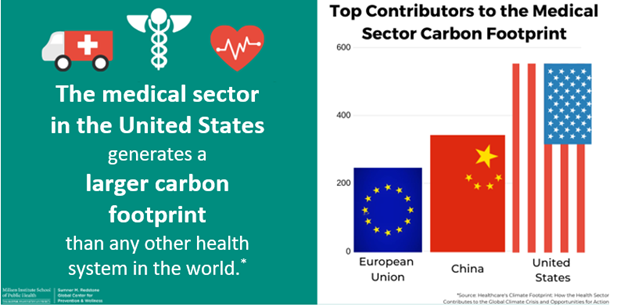

One approach to building political will is to begin with changing our behaviors, those of our families, and our institutional practices. Although advocacy is essential, there are more immediate individual and collective actions that we can take. The medical sector generates 10% of US GHGs and 40% of the medical sector’s contributions are from hospitals’ use of fossil fuels. Conversion of hospitals’ use of fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy would substantially reduce that source of GHGs.

Anesthetic agents are responsible for 0.7% of GHGs in the U.S. Shifts away from fluorinated agents and nitrous oxide to anesthetic agents that have a limited impact on GHGs would contribute to an additional reduction. Changes in hospital procurement to more plant-based diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, incentivizing reduced car use among medical staff and employees, reducing food waste, and counseling our patients to do the same would benefit both individual and planetary health. Several health systems have actively begun to reduce their carbon footprints. For example, Kaiser Permanente became the first carbon-neutral health system in the U.S. last year and the Cleveland Clinic has pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2027. Although the medical sector’s contribution to climate change is not as great as that of the transport system, it is our responsibility, and we need to act to reduce our impact. Now.