The human skeletal system is an integrated framework of more than 200 bones and connective tissues that maintain body structure and facilitate movement. Over time, the joints that connect the bones in our skeletal system undergo wear and tear that limits their flexibility. Abnormal or excessive strain on the joints can lead to arthritis, an umbrella term used to characterize inflammatory diseases that affect one or more of the body’s 360+ joints and surrounding structures.

The most common form of arthritis is osteoarthritis (OA), a condition in which the protective cartilage that normally prevents bones in a joint from rubbing together is slowly eroded. In advanced stages of OA, a collapse of the joint space causes bones to rub directly against one another, rendering any movement of the joint extremely painful. Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of long-term disability and ambulatory care costs paid by private U.S. insurers. Between 2008 and 2014, per-person annual U.S. medical costs directly attributable to OA averaged $11,052. A large proportion of persons affected by OA report severely diminished quality of life across multiple domains of functioning.

Osteoarthritis risk is 4 times higher among women, and 5 times higher among men with obesity, relative to adults with BMIs in the normal range. The obesity epidemic and the aging of the population is expected to double the prevalence of OA by 2040, increasing the number of affected adults from 32.5 million to more than 78 million. Two distinct mechanisms contribute to the association between obesity and OA:

-

Obesity increases the risk for osteoarthritis through added stress on weight-bearing joints. Basic movements such as walking and bending put pressure on the bones and joints in our lower extremities. The largest joint in the human body, the knee joint, bears the brunt of force during locomotion and is especially prone to injury. The force exerted on the knee joint is directly proportional to body weight. For a 200-pound adult, a 10-pound weight gain translates to an additional 15 pounds of force on the knee joint when walking, 30 pounds when climbing stairs, and 50 pounds when squatting to tie a shoe. Two-thirds of adults with obesity are expected to develop knee OA, with considerable variation in the severity and progression of disease.

-

Obesity increases production of inflammatory factors that may exacerbate osteoarthritis in non-weight-bearing joints. Adipose tissue (i.e. body fat) is now recognized as a metabolically-active tissue that synthesizes and secretes hormones and cytokines. Cytokines are the key regulators of inflammatory processes throughout the body. Increased expression of these molecules likely mediates the association between excess body fat and development of arthritis in upper extremities (e.g. hand, shoulder).

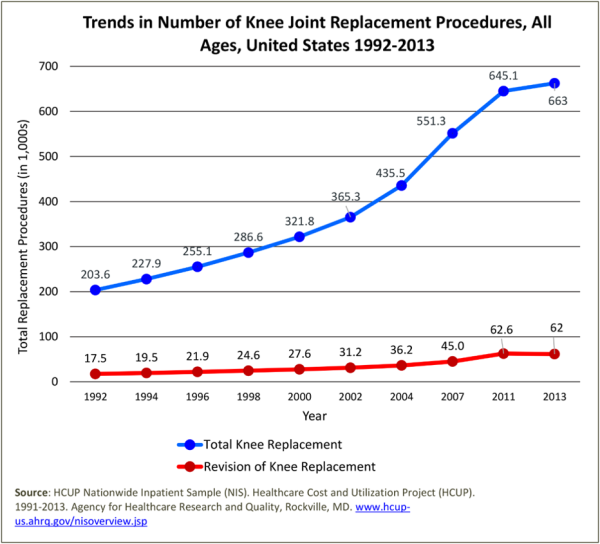

Treating obesity will not reverse the damage done by osteoarthritis—orthopedic surgery is currently the only method of restoring cartilage in affected joints in humans (Figure 1). Despite shorter hospital stays (8.9 vs. 3.4 days), hospital charges related to knee replacements increased five-fold between 1998 and 2013 ($8.4 billion vs. $41.7 billion, inflation-adjusted USD). Importantly, the average age of persons receiving knee replacements dropped by nearly 2 years during this time period, suggesting that obesity may be increasing premature morbidity. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive surgical treatment for OA despite a greater disease burden, further exacerbating obesity-related health disparities. New research suggests that the combination of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and OA should prompt careful attention from health professionals, because this subtype of “metabolic OA” is associated with significant increases in cardiovascular disease risk, severity of pain, and need for total joint replacement surgery.

FIGURE 1

Healthy weight management is the frontline strategy for primary and secondary prevention of OA. A decrease in 2 BMI units can decrease OA risk by 50%, and 5-10% reductions in excess body fat can significantly slow OA progression and prevent long-term functional impairments. Medical obesity treatment strategies such as very-low-calorie diets, pharmacotherapy, and/or bariatric surgery are particularly appropriate for individuals with OA and severe obesity. Because physical activity is critical to healthy weight management but can be painful for individuals with comorbid OA and obesity, primary care providers should connect clients with physical therapists or professional trainers who can prescribe exercise regimens that minimize pain and additional damage to joints.