Over the past two decades, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) invested in two major multi-center studies aimed at obesity prevention in low-income Hispanic and African American children: the Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment Research Consortium (COPTR) and the Girls’ Health Enrichment Multisite Studies (GEMS). Both COPTR and GEMS deployed state-of-the-art, culturally-appropriate interventions and behavior change strategies with the goal of preventing excessive weight gain in early life. Despite their sound design, neither the GEMS nor COPTR studies altered the trajectory of weight gain among participants compared to controls.

The failure of these studies to prevent obesity is disappointing and unexplained by the data included. The contact hours for the GEMS and COPTR trials were consistent with those recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for weight loss in children and should have been sufficient for the prevention of weight gain. The interventions targeted multiple levels of influence (e.g. families, youth organizations, schools, primary care providers) and were sufficiently engaging for participants. Retention rates for treatment and control groups ranged from 89-96% and were exceptional for this type of investigation.

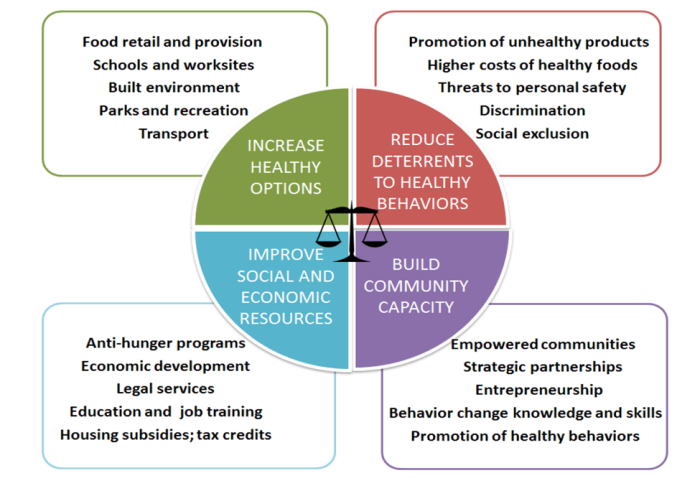

In a new commentary published in Pediatrics, I suggested that the social conditions in the communities in which these trials were conducted may help to explain the disappointing results. Between 30% and 50% of families in the COPTR trials reported food insecurity. Nearly half of families from the most recent COPTR trial in Cleveland moved during the 3-year study, and 10% moved three or more times. The arm of GEMS based in Oakland, CA, needed to change venues six times, partly because of episodes of violent crime near the intervention sites. These conditions may help explain why behavioral interventions to prevent obesity had such limited success among families. A plant rooted in poor soil is unlikely to thrive no matter how much it is watered. Sustained improvements in diet, physical activity, and perceived stress are predicated upon suitable social, economic, and built environments that make those changes possible. The results of the GEMS and COPTR studies suggests that more fundamental efforts to address adverse community environments, such as building community capacity and improving social and economic resources, may be required to mitigate obesity-related morbidity and mortality among low-income and minority populations (Figure 1).

At the very least, future efforts for obesity prevention and control should be tailored to the community context to assure that the strategies that are implemented engage and build capacity within communities. This approach requires coupling behavioral interventions with strategies to address the social determinants of health. We will not likely resolve the disparities in the prevalence of obesity without addressing the inequities that cause them.

FIGURE 1. Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention: A New Framework (Kumanyika, 2017)