Over the past decade, researchers have explored the link between social relationships and individual health outcomes. Obesity—like food intake, depression, physical activity, and healthy behaviors—clusters within social networks. Also, positive collateral health effects accrue for non-treated individuals when a spouse or close family member undergoes bariatric surgery or intensive behavioral therapy for weight loss. Yet, the mechanisms governing this clustering phenomenon within networks remains poorly understood.

The non-random clustering of individuals with obesity in social networks include: homophily, shared environment, and social contagion (Figure 1). Implications for obesity prevention and treatment policy differ significantly depending upon which of these causes is most salient.

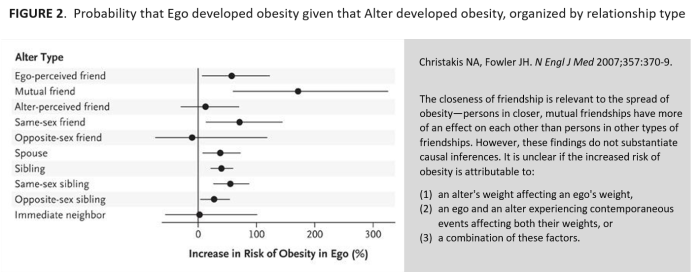

The third and most controversial of these effects—social contagion—was popularized by an influential 2007 study that mapped the spread of obesity within a 12,000-person social network over three decades. The researchers found that a person’s likelihood of developing obesity increased significantly if a friend (57%), sibling (40%), or spouse (37%) developed obesity over a period of years (Figure 2). In responding to these findings and similar follow-up studies, critics of the social contagion model of obesity do not deny the plausibility of such a phenomenon but assert that observational studies to date have not incorporated information on individual characteristics, choices, preferences, and environments to the extent necessary to reliably distinguish social network effects (i.e. contagion) from other confounds of weight gain (i.e. homophily and contextual factors).

Similar criticisms apply to a new study published in JAMA Pediatrics. Using data from military families scattered across 38 installations nationwide, the researchers found that a 1% higher obesity prevalence in the installation county was associated with higher body mass index [BMI] (0.08 units), 5% higher odds of parental obesity, and 4% higher odds of child overweight/obesity among military families. The authors concluded that (1) “exposure to communities with higher rates of obesity is associated with higher BMI and greater risk of overweight and/or obesity” and that (2) “this may suggest the presence of social contagion.”

Does this study provide evidence of social contagion as a cause of obesity? Maybe. While the results do not preclude social contagion as a possible driver of obesity status in these families, social contagion requires comparisons over time. However, the JAMA study only included cross-sectional data and only one time point. Without a baseline measure of participant weight status prior to relocating, the effect of county obesity prevalence on incident obesity cannot be established. The study also lacked a social network analysis, which would have provided insights on intra-family interactions and the directionality of observed associations.

Unsurprisingly, provocative headlines from major news outlets like Newsweek (“Weight Gain Is Contagious and You Could 'Catch' Obesity From Your Neighbors, Study Finds”) overstated the study’s rather limited findings. Claims about the interpersonal spread of health phenomena have particularly important implications for policies that guide obesity prevention and treatment efforts. Given the near impossibility of randomizing families to communities (or individuals to social networks), future studies involving military families hold great promise. Because the effects of self-selection and shared environments are reduced among military populations and their families, it may be possible to establish the multigenerational spread and remission of obesity in social networks.