Obesity is characterized by the accumulation of excess body fat (adiposity) that presents a risk to health. Although excess body weight is often associated with excess adiposity, obesity is a complex disease that should not be conflated with high body weight alone. The location of fat deposition is an important determinant of morbidity.

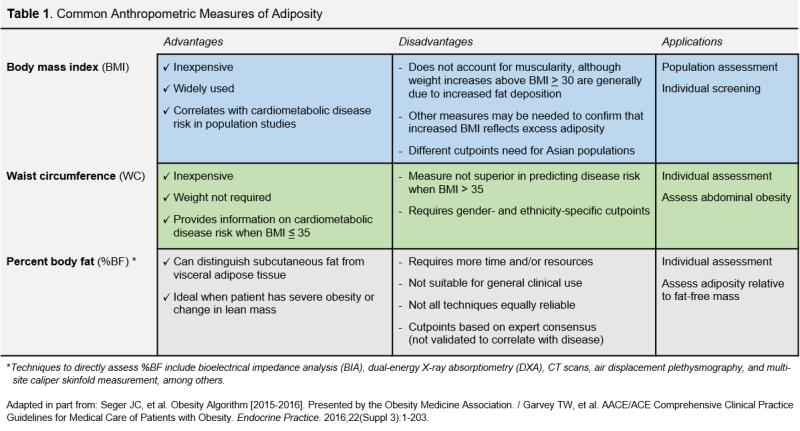

Common measures for evaluating obesity in clinical practice include body mass index (BMI = kg/m2), waist circumference (WC), and percent body fat (%BF). Clinically-relevant strengths and limitations of each measure are summarized in Table 1.

BMI is the oldest and most widely referenced measure of adiposity. BMI, originally called the Quetelet index, was developed by Adolphe Quetelet in the 1800s, proposed as a population-level health indicator by Ancel Keys in the mid-1900s, and recommended as a clinical measure of obesity by the National Institutes of Health in 1985. Given the multitude of factors not considered in BMI calculation—including gender, ethnicity, age, and lean mass—debate about the appropriateness of BMI as a crude measure of adiposity continues today. Wide dissemination and misinterpretation of several studies examining the association between BMI and cardiovascular disease gave credence to the now-debunked“obesity paradox” and fueled public skepticism regarding BMI’s validity as a health indicator. A recent survey of Arkansas parents who received BMI report cards found that most respondents did not believe that the report accurately showed their child’s health status, despite acknowledging excess adiposity as a component of increased disease risk.

Designing an obesity indicator that improves upon BMI has proved challenging. To facilitate effective policy interventions and/or clinical decision-making, health indicators typically include cutpoints that allow a reasonable estimate of morbidity and mortality risk (e.g. BMI of 32 indicates obesity using U.S. cutpoints). Derivation of valid cutpoints that accurately predict disease risk requires extensive cross-sectional and longitudinal data and a thorough understanding of physiological mechanisms that link the measure to disease outcomes of interest.

The impact of excess adiposity on morbidity and mortality varies as a function of gender, ethnicity, age, and body fat distribution. Therefore, obesity screening methods and associated cutoffs necessarily differ for developing children, adolescents, and adults. Evidence suggesting that BMI and WC also differ by ethnicity, as surrogates of body fat and predictors of cardiometabolic disease, has led to recent development of separate obesity cutpoints for South Asian, Southeast Asian, and East Asian adults [BMI ≥ 23; WC ≥ 85 cm (men) / WC ≥ 74 to 80 cm (women)].

While cautions against the use of BMI as a diagnostic tool for obesity are warranted, convenience and simplicity render it valuable in health screenings and epidemiologic studies of non-elderly adults. Recognizing the limitations of BMI, current guidelines for the prevention and management of obesity recommend additional measurement of WC, or %BF to better gauge potential health risks associated with adiposity and advise on the best course of treatment.