Because the human liver filters toxins and redistributes nutrients, it is one of the most important and versatile organs in the human body. While a healthy liver composed of about 5% fat by mass can regenerate when damaged, the accumulation of excess hepatic (liver) fat can impair liver functioning and silently increase an individual’s risk for diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

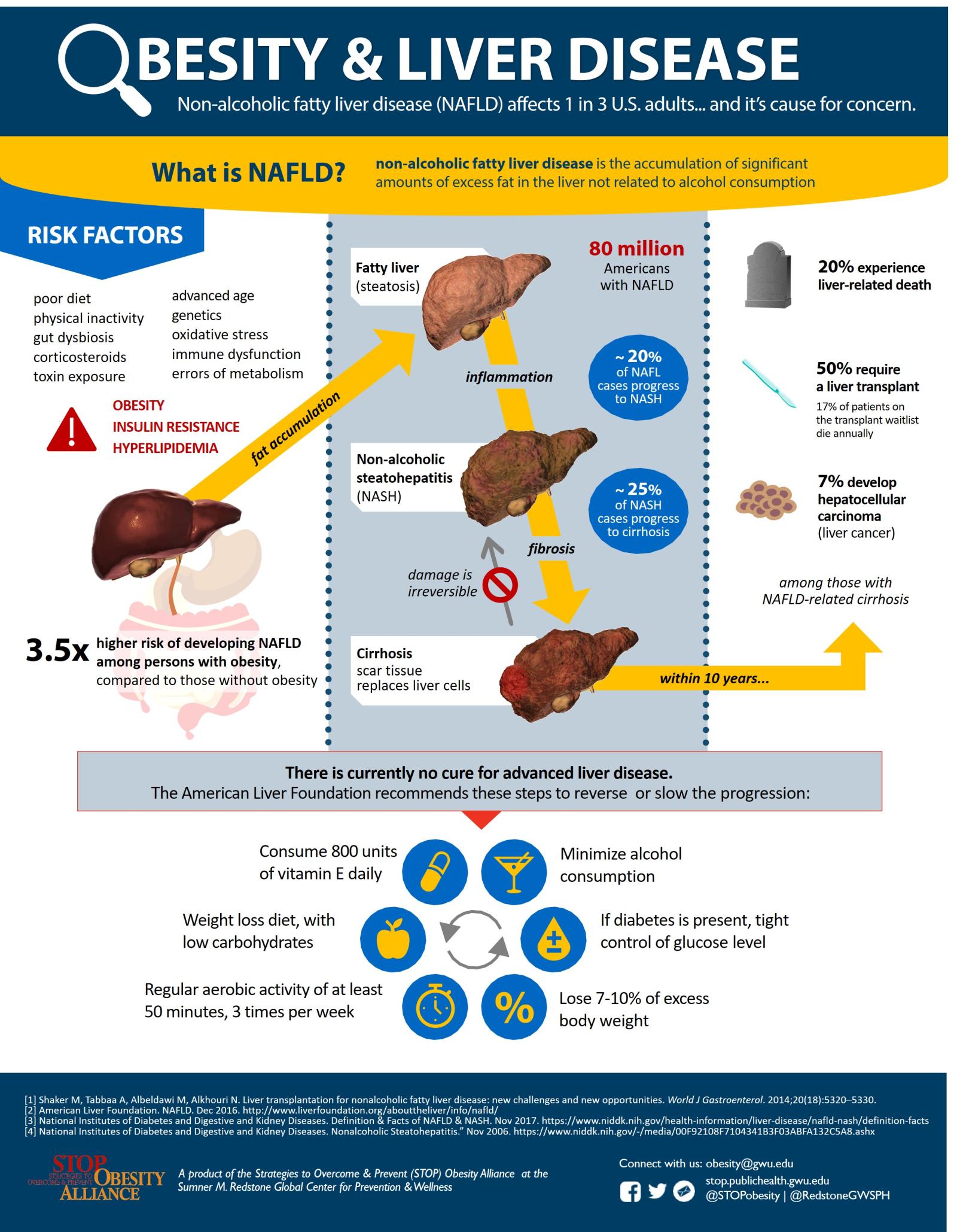

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—an umbrella term for the spectrum of fatty liver diseases not linked to alcohol consumption—affects 1 in 4 Americans and is now the most common cause of liver dysfunction. Researchers estimate that NAFLD-related liver disease will contribute to nearly 800,000 excess liver deaths between 2015 and 2030. The severity of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis (fatty liver) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a condition that can lead to irreversible scarring (fibrosis, cirrhosis) and liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) (Figure 1). NASH is currently the third leading cause of liver transplants and was projected to increase by 63% (16.5 million to 27 million cases) between 2015 and 2030.

The onset of NAFLD and progression to NASH are closely linked to insulin resistance and abdominal obesity in both adults and children. The prevalence of NAFLD (65%) and NASH (25%) is higher among persons with obesity and type-2 diabetes than in the general population. Researchers have established a dose-dependent relationship between obesity and NAFLD: the relative risk of NAFLD increases 20% for every 1-unit increase in BMI.

Diagnosis is a challenge. Current clinical guidelines recommend that persons with obesity or metabolic syndrome be routinely screened for NAFLD. Although NAFLD can be diagnosed by ultrasound or blood tests (AST / ALT liver enzymes), liver biopsy is required to assess fibrosis, the primary marker of progression toward more severe liver disease (e.g. NASH). Liver biopsies are costly, and the number of suspected NASH cases far exceeds the number of health professionals trained to perform and interpret liver biopsies. It is likely that NAFLD and NASH will continue to be underdiagnosed until non-invasive screening and diagnostic techniques are validated and widely available.

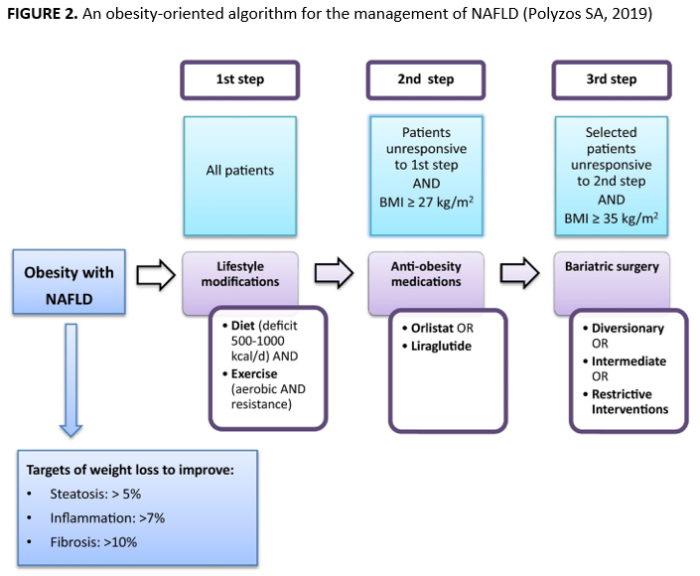

Treatment is a challenge. Treatment options vary by the stage of disease progression. All current guidelines recommend weight reduction through lifestyle modification as a cornerstone of NAFLD management, possibly with other therapies as needed to produce significant weight loss (Figure 2). Resolution of NASH is achieved in 65–90% of patients achieving ≥7% weight loss, while clinically-significant improvements can be observed in steatosis with ≥3% weight loss, inflammation with ≥5% weight loss, and fibrosis with ≥10% weight loss. However, liver transplantation is the primary treatment when NAFLD progresses to cirrhosis or liver cancer. NASH-related additions to the U.S. liver transplant waitlist — already 13,000 candidates long—is predicted by the prevalence of obesity nine years prior and expected to exceed 2,000 annual waitlist additions by 2030. Seventeen percent of patients on the transplant wait list die annually, and not all individuals with end-stage liver disease are candidates for transplantation.

Primary and secondary prevention are key. Resolving NASH before it progresses to cirrhosis or cancer is paramount. In the absence of NAFLD-specific pharmacotherapies, greater investment in effective obesity prevention and treatment approaches may be the best available strategy to slow the growth of NASH cases and mitigate NAFLD burden.